Bella’s Curves

A straight back – isn’t that what we want for a good strong horse?

It depends . . . on our definition of “straight” and also on our idea of structural and muscular strength.

During capture wild horses are subjected to tremendous stress and often, injuries to their spine (as well as to their mind and heart, which also affect the body). Every individual has a different response to extreme stress. A horse who tends to respond to fear or pain by freezing, or by fleeing, may be more likely to end up with a high head, a rigid spine and thus a “straight” back.

When she arrived as a yearling , Bella’s back was injured. Whenever she moved, her spine from poll to tail stayed straight as a yardstick due to pain and abnormal muscle tension. A year later, after bodywork and other treatment, she had regained a comfortable spine and flowing movement.

I have observed this same condition in other mustangs, sometimes horses that have been held in captivity for several years. Orthopedic-type massage is important to release cramped muscles and restore normal movement. In some cases I have worked with, the mustang’s back relaxed only after treatment with a homeopathic remedy, Thuja occidentalis, that is often used to relieve signs of an unhealthy reaction to vaccination. Sympathetic bodywork that relieves pain and tension can be significant in helping a horse learn to trust people.

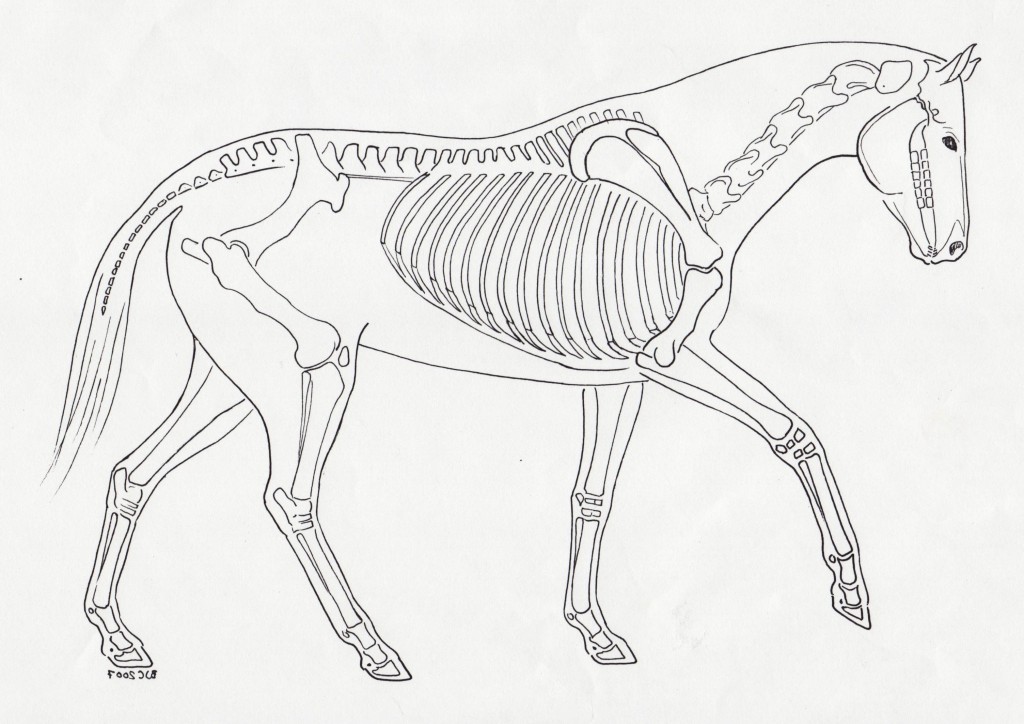

A horse’s backbone, like ours, is designed to protect the spinal cord, yet be flexible enough to bend as the body moves. As the horse changes position, adapts to a new gait or speed, bends to one side or the other, stops or backs, the whole spine moves too. Each joint in the spine has a particular design and range of motion, and each section of the spine has its own range of motion. The most important joints occur where one spinal section intersects with another. These points are at the poll (between the skull and the atlas, or first vertebra), at the base of the neck (between the cervical and thoracic vertebrae), just past the middle of the back where the rib cage ends and the lower or lumbar back begins; at the lumbo-sacral junction where the power of the hindquarters is transferred through the back itself; and where the sacrum and tail meet.

The photos following help us see how a horse can recover a healthy spine, and as she grows, maintain a strong “straight” back through training and into adulthood. The spine does not complete its growth until the horse is six to eight years old. For a long, sound life it pays to be patient.